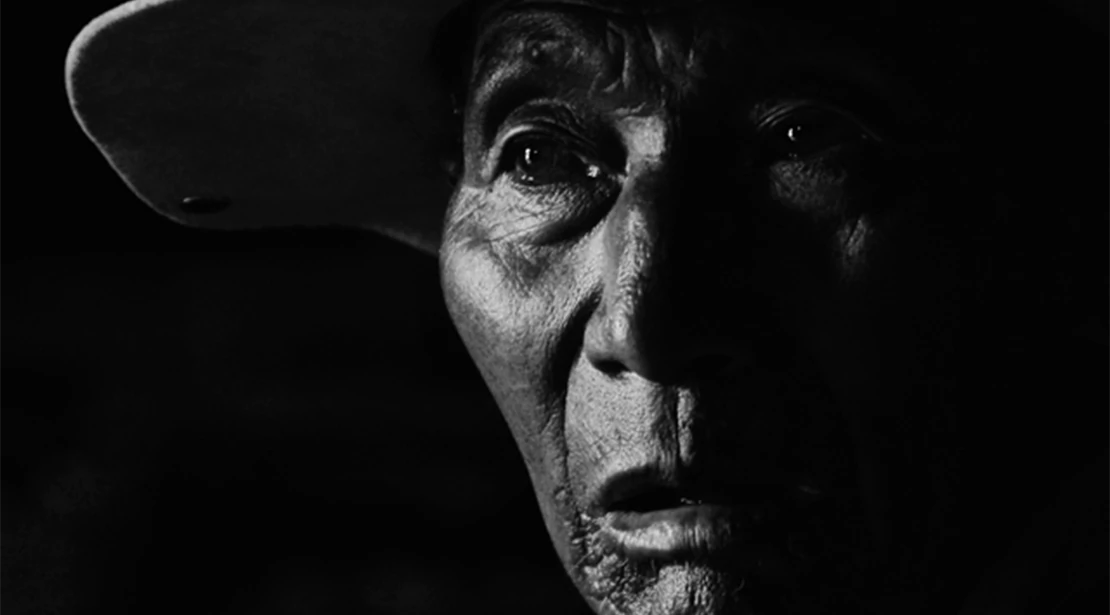

There are idols one meets that one never expected to even have. This is exactly the case for me as I stare at a man who, not a month ago, was barely on my mental map. But here he is: imposing, ancient and muttering with a voice that sounds as if it is emanating from decades away.

Tenzin is one of the last remaining lados - muleteers or men with ‘hands of stone’ - who I’d first heard about while tracing a portion of a trade route in Qinghai Province. Legendary and epic, these ancient routes criss-crossed the land of snow, ushering everything from resin to tea along into the big silences that are the Himalayas. But routes needed bodies to usher goods. They needed carriers, guardians, and beasts of burden. Tenzin was all of these in his day. And he is one of the last that can recall those days.

Wind tears at the interior of the tent we're tucked into. There are prayer beads in Tenzin's hand, painstakingly and lovingly massaged by a large thumb. Tenzin is as elegant as he is imposing. His grace belies a man that in his time crossed (and survived) the Himalayas from end to end, and top to bottom.

Tenzin is “somewhere in his seventies”. He reminds me that birth dates weren't always remembered or written down in the nomadic lands where he was born. “What does it matter?" he asks at one point, to no-one in particular. It may not matter, but I know that the number of these old raconteurs from a different time is dwindling.

Winter and its impeccable brutality haven’t yet fully arrived, but anything at these altitudes - almost five kilometres into the sky - has an edge. Tenzin's tent is one of eight yak-wool tents ratcheted down into the frost-hardened turf. With us are Norbu and Lobsang, both hardened mountain men themselves, though they admit they are in awe of the being that sits before us.

Wrapped in furs, he tells us that if we wish to ask questions we must listen to his answers. These first words hint at his value system, which regards respect and time as vitals. And so began what I thought would be a couple of hours of questions and listening. Two days and nights later we are still lodged in his tent, riveted by the words and observations of this leather-skinned scribe.

Our host has told us that he is preparing for his “next life”. The whole view of endings and beginnings in these lands is smudged with immortality in a variety of forms. The idea of loss, while felt, feels slightly less final up here…slightly less physical.

To travel upon the Himalayan ‘roads’ or routes (called ‘lam’ in Tibetan) was the stuff of lore and almost mystical feats. Traders like Tenzin were part renegade, part guardian, part negotiator, part survivalist, and perhaps fatalist.

Everything in the tent is imbued with the acrid smoke of yak dung and the deeply entrenched tang of butter. Not even the winds can muffle these essentials in Tenzin’s life. Tea, movement, a rare tenacity and knowledge of the mountain’s every breath make up this man’s energy, but even he needs the comforts of fuel and warmth.

“The mountains are never asleep”, Tenzin says at one point. The words are startling in a simple philosophical way and in the way they personalize the not-so-distant spires and forces at work beyond this tent.

While the talk of trade and grand isolated economies fascinate, it is these little observations of the landscape, the elements and the personalities of mules, mountains, and mortals that cling to the ears and mind.

When describing a long ascent over an epic snow pass, Tenzin looks down into the fire pit in the tent and explains in his understated but authentic way how the ice would build in the mules’ hooves so severely the mules would stop and refuse to move.

There was silence in the tent as a picture formed in my mind of Tenzin’s description (a description that matched our own experience trudging through a blizzard two weeks previous) that none could fill with anything meaningful. When confronted with such a sage, one waits and is happy to do so. When Tenzin raises his eyes every once in a while both Norbu and Tenzin look to the ground in respect like boys.

What followed from Tenzin was one of those exquisite moments when a truth is told that transcends a space or audience – it is something that extends into every particle and cell. No eloquence, no verbose descriptions or hyperbole required, just plain truth. “Mountains are the great instructors. They can give or take depending how you look at them but they can get angry with us”.

He doesn’t clarify this, instead leaving the words out there for me to ponder and wonder at. This man and his memories and old understated truths were here in this tent while three of us waited for his every breath and movement. All we had to do was listen and care. It was perhaps wrong to hold this being in such esteem but his straightforward nature, and the fact that he had endured such a life – and indeed thrived – in these spaces was enough to count for some measure of magnificence.

The land of snows holds more than simply risk. It holds comfort. “All came with weight in the mountains”, a climbing mate of mine once told me and it was truth.

Mountains have long enveloped their residents in an embrace that is as protective as it is isolating. To leave them and wander was a risk to many who grew up in their long wide shadows.

Tenzin was born on the Tibetan Plateau to parents who had 40 yak, 100 sheep, three other children, and who moved three times annually, hitching up their entire tent and life and moving to better grazing. He’d had enough food and had grown strong and tall (he was 6ft 3) and found wandering to his liking. He had wandered, risked, and traded for four decades learning three languages and building up a great respect for trade and traders.

He’d watched when four-wheeled vehicles and their predecessors, the asphalt roads, had begun their incursions, making the caravans of hoof and foot less and less necessary. He’d outlived feuds over who had rights to trade salt, and who had priority to travel the rickety pathways cut into stone. While not a pessimist, at one point he mentions how “cars will make people forget how to move through the lands and understand them”, and it too has the feel of a kind of truth.

At intervals as he talks he instructs one of us (usually Norbu) to fix butter tea to keep him hydrated and alert. Norbu, a tough and silent force, bows his head with respect and fixes the pungent liquid more competently than the rest of us could manage. Tenzin points to the tea in his worn and stained bowl and reminds us how this “need” came from a long way away. Items of luxury were items where distance needed to be covered (even now).

At one point after sipping Tenzin tells us that he will nap a bit, but insists we remain so that when he wakes, he can continue his rambling. Norbu’s tough face looks sideways at me with a smirk.

Old Tenzin is enjoying himself and the company and we are enjoying these special moments with one of the integral players in the history of trade on the top of the world.

Read about Jeff's adventures with a medicine hunter here.